Tanjore paintings: The guild of gold

How gold foil on gesso made its way to Thanjavur paintings and why it endures

“Aracha maave arachandirukkom,” says Swaminathan Vishwakarma, 55, an award-winning Thanjavur painter.

He means that his community has been doing the same old, same old. Currently, the demand for innovation in themes and design details in Thanjavur paintings is close to negligible, and so is their incentive.

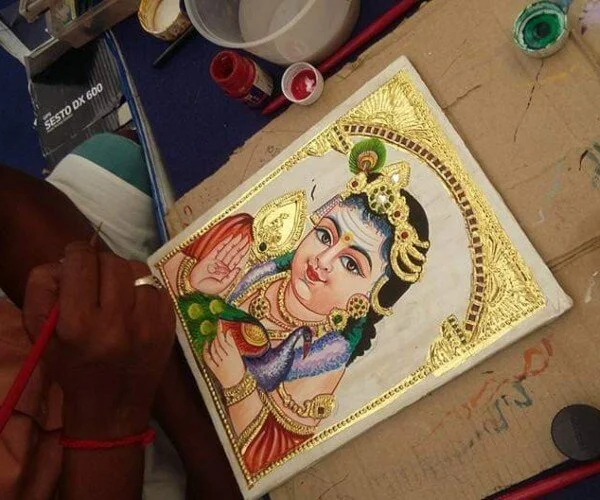

The making of a Tanjore painting | Courtesy Swaminathan Vishwakarma

When Thanjavur paintings received the Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2007, commercial interest in the art had picked up, long after a brief spike in the early 1990s. Following that, relatively cheaper, fake-gold foil sheets started making an appearance in the market—it encouraged hobbyists to keep the art alive, but also aided insincere profit-making motives.

Barring that, the form itself has barely evolved. Its characteristic idiom—the striking gold foil on gesso (a white paint mixture) with embedded gemstones, flat vivid colours, and divine figures—has stayed largely the same for close to a century.

This stagnancy, however, was not typical to Thanjavur art. In fact, the indispensable use of gold film on gesso would not have even come to be if it were not for the many initial experiments by the region’s artisans.

Gilded Beginnings

The Thanjavur painting as we know it today was a result of the region’s artisans imbibing the influences of “the Vijayanagara murals, and through it Deccani painting, court painting…traditional sculpture in wood…and…folk painting,” writes art historian Jaya Appasamy in Thanjavur Painting of the Maratha Period. The book is a detailed study of the art form, which has its roots in the 18th and 19th centuries.

When the Madurai Nayaks ruled as an extension of the larger Vijayanagara Empire, “the finer aspects of the Telugu culture trickled down after blossoming in the Vijayanagara kingdom,” says culture writer Veejay Sai. Later, when the Marathas gained control, they continued to patronise the arts in the region.

This patronage led to a free flow of thoughts and techniques between visiting and resident artisans.

“The application of gold was borrowed rather than indigenous. There is no evidence that such an art existed in the past in southern India,” says Appasamy in her book, indicating that while folk art gave Thanjavur the idiom of “plump and sumptuous figures” with “large heads” and sculpture influenced the gesso, it is Deccani and Rajasthani painting that inspired its use of gold.

By themselves however, the Thanjavur painters of yore were already “highly skilled” with jewellery, sculpture, and architecture.

What seems to have guided them however, was a dedication to durability coupled with a collective bhakti bhaava (devotional expression) over individual expression. It is this unique combination that has given Thanjavur paintings their biggest strength—the gold foil on gesso. It has also given it its biggest contemporary weakness—its decades-old stagnancy.

Gold Symbolises Fire, Purity, Wealth

Thanjavur art’s basic canvas-making process itself is a distinguishing feature. Two layers of cloth are pasted over a plank of jackfruit wood, with gum made from tamarind seeds; then, a paste of lime is painted over it. Once this dries and is polished with stone, a drawing is made demarcating sections. Finally, the artist sticks on the gold or gemstones with a gluey limestone paste, before painting in the colours.

Gajalakshmi

“This wasn’t just an artistic or decorative choice. It was scientific,” says Veejay Sai. “Even the way they made dyes was such that it would protect the painting from insects. The paintings were made to last long,” he adds.

Over time however, ply boards, Fevicol and acrylic paint have replaced their natural, durable predecessors.

“But the love for gold has endured,” says jewellery historian Usha R. Balakrishnan.

Traditionally, for centuries, families in South India have preferred gold jewellery over any other. Gold is non-reactive, does not rust or tarnish: it is pure, and therefore, auspicious.

“Gold has always symbolised fire; it is a symbol of purity. It symbolises wealth, and is an emblem of Lakshmi [the goddess of prosperity]. Threads of gold are woven into saris, it is in the gopuram (ornate entrance towers) of temples. It has a strong ritualistic significance within the Hindu dharma so to speak,” says Balakrishnan. "Even the Panchadhatu (traditional, sacred metal) for example has a small amount of gold added to it.

This very property also gave gold social currency. In many communities even today, a girl is sent to her marital home with some gold as part of her personal wealth (streedhan, the protection of which is enshrined in the law) — the husband or his family cannot exercise claim over it.

A Sense of Pure Devotion

There are also instances from early 18th century Thanjavur, when art that depicts gods adorned with gold jewellery, was presented at weddings. Incidentally, musicologist P. Sambamoorthy’s biography of the saint-composer Tyagaraja (mid 1700s-early 1800s) mentions that a student, Walajahpet Venkataramana Bhagavatar, had presented a painting of Kodanda Rama (Rama with Bow) to his guru on Tyagaraja’s daughter’s wedding.

A photo of this painting found on Carnatic music forums online shows a clear early-Thanjavur style. The gold iconography is all there—the face of a yazhi, a mythical creature considered more powerful than a lion, in the background; an aarti cup (for ritualistic prayer) in the foreground.

Ram, Lakshman and Sita stand below a gold-coloured stylised frame of arches reminiscent of temple architecture. Sita has lines of gold at her waist, indicating a belt or a layered, waist-hanging jewel. Ram and Lakshman’s bows are both strong strokes of gold.

This theme, of Ram with a bow—the Kodanda Rama is still popular. The iterations that came after Tyagaraja’s time had started to edge out the flat gold-yellow painted surfaces in favour of gold gilding on gesso. This led to the gold architecture that framed the canvas even more intricately embossed with floral swirls. Over time, Sita began to have a prominent golden nose ring, similar to the large circular Maharashtrian nath. Soon, in many versions of this theme as well as in others, artists had begun to emboss the torsos of the gods entirely in gold.

“The sacred icons…and their highly decorated character was an expression of devotion,” writes Appasamy. She quotes Philip Rawson, an expert in Eastern art: “the attitude towards ornament reflects an instinct deeply rooted in the Indian character. To ornament is also an expressing of respect…or other auspicious properties.”

The fact that Thanjavur artists would not sign their name on their paintings further shows devotional loyalty in the practice.

Current Sparkle and Cost

Swaminathan working on a Tanjore painting of Murugan | Courtesy Swaminathan Vishwakarma

In what feels like a hat tip to the continuation of gold’s history with Thanjavur paintings, artists today say that commercially available gold foil comes from Rajasthan and Gujarat.

While artists prefer to stick to these, out of good conscience, they are also ready to cater to the budgetary needs of the market. For example, Swaminathan Vishwakarma has a simple price chart on his Facebook and Twitter pages, which his graphic designer son manages for him. A 12 x 10 painting with original gold will cost ₹4,500 while the same size with “second quality” gold will be cheaper only by a thousand rupees. This difference, of course, compounds as the sizes get bigger. He sets the price for a 4 feet x 3 feet work with pure gold foil at ₹1,20,000, while the second quality version costs ₹80,000.

Owning and adapting to market reality is the entrepreneurial innovation expected of Thanjavur artists now. However, most are reluctant to making changes in the designs. The architectural elements understandably remain constant, inspired as they are by ancient temples. Similarly, from the reticent way that the artists talk about changing the jewellery on their gods, it seems like these elements form symbolic and religious iconography—this has no scope to change with the times either.

“…the iconic style of Thanjavur painting fulfilled a function that was not primarily aesthetic…and became repetitious precisely because it was sacred,” writes Appasamy. Regular portraiture, which Thanjavur painters did briefly under the British, did not necessitate the grandeur typical to their art.

To this day the Navaneeta Krishna (baby Krishna with a pot of butter), Gajalakshmi (Goddess Lakshmi with elephants), Kodanda Rama all continue to be depicted under the gilded temple arches with flowers and the yaazhi. They continue to be adorned with a traditional golden kaasu malai (a chain made of small gold coins), medallion-like-pendants, and crowns just as they were over a century ago.

“I have been doing just what my forefathers did,” says the 70-year-old artist V. Gopi Raju. “As for my children, they accommodate doable requests, like if someone wants more stones in the work. But if it is something very different, they tell them it can’t be done.”

This story was first published here