Possessing more than one language has never harmed anyone: Geetanjali Shree

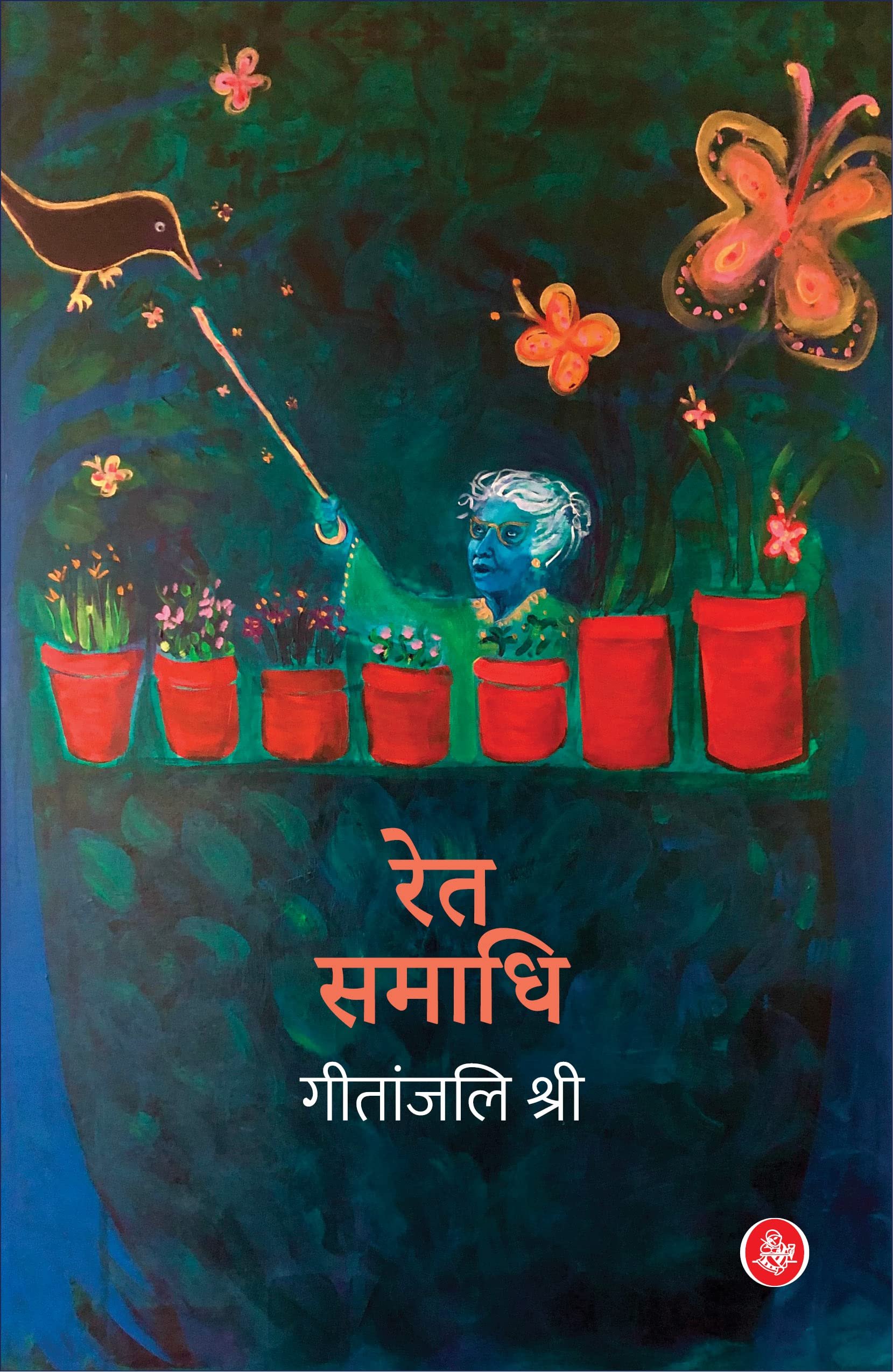

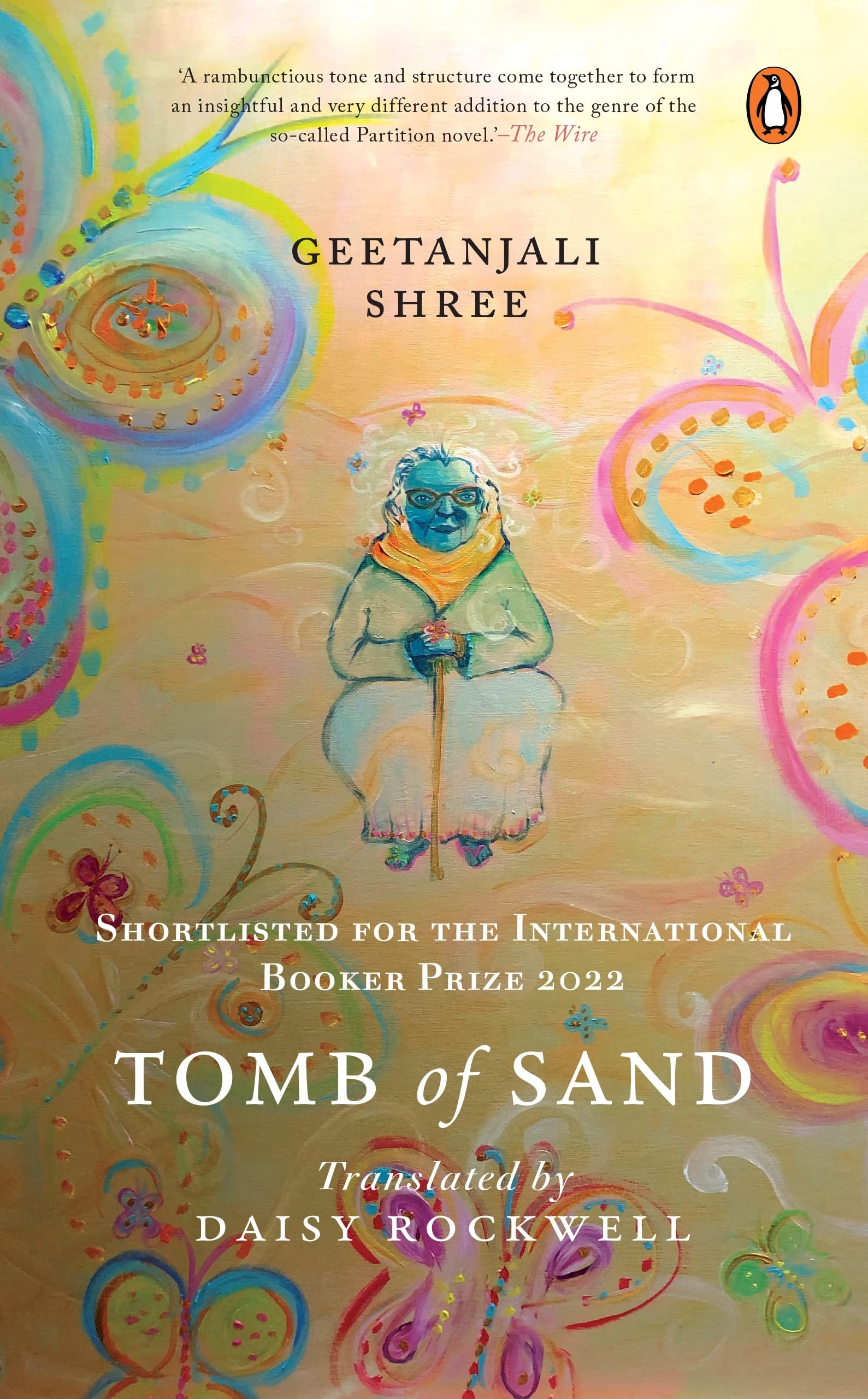

The writer, whose ‘Ret Samadhi’, in translation as ‘Tomb of Sand’ is on the International Booker shortlist, on process, writing in Hindi, and more

Author Geetanjali Shree. Image courtesy Penguin Random House India.

Most successful novels have blurb descriptions such as “gripping”. Some of them are praised for hooking the reader from the opening page. Tomb Of Sand, which made it to the 2022 shortlist of the International Booker Prize last week, does not fit this description.

In the book spanning close to 700 pages, the first quarter meanders, with the third-person narrator seeming to speak from a fever dream—an effect heightened by the fact that the dialogue is never demarcated by quotation marks. In an age when writing and “content” work to be the most attention-grabbing versions of themselves, Tomb Of Sand does not bother. Confident in itself and its world, it demands a certain discipline and stillness from the reader.

It begins with a chapter titled Ma’s Back, in which an elderly woman, is grieving and depressed. Her husband is dead. Her back turned to the world, she refuses to get out of bed.

The opening luxuriates in weaving in and out of a backstory, told with distracted charm. If impatient, you are bound to give up. Suddenly, though, sentences of deep, ancient wisdom will hit you: “Those who consider death to be an ending took this to be hers. But those in the know knew this was no ending; knew she’d simply crossed yet another border.”

And this is what the novel is about. The nature and effect of invisible, intangible, yet incontrovertible borders. Between countries, the realms of the mind, and people. Yet there is humour and lightness, undercutting the book’s physical and thematic weight. It takes Ma over a hundred pages to get out of bed but once she’s up, a sense of a plot takes shape. Its flow may not be for everyone but its spots of poetic wisdom resonate widely.

Shree, 64, is a well-regarded writer whose contribution to Hindi literature has been recognised over the years with awards like the Indu Sharma Katha Sammaan, Hindi Akademi Sahityakar Sammaan and Dwijdev Sammaan. In addition to short story collections, Shree has four more novels to her credit: Mai (1993), Hamara Sheher Us Baras (1998), Tirohit (2001) and Khali Jagah (2006).

Mai, about three generations of women in a middle-class, north Indian family and the way they navigate patriarchy, is narrated by Mai’s daughter Sunaina, giving the reader a layered understanding of their lives. In 2000, its English translation by Nita Kumar was shortlisted for the Hutch-Crossword Translation Award. Now, 22 years later, and two years after its Hindi original Ret Samadhi came out, Tomb of Sand too finds buzz with English readers, this time globally. It, too, focuses on women—a mother and daughter, with the latter discovering the unconventionality of her elderly, recently widowed parent.

Over the years, Shree’s stories have also found Gujarati, German, Japanese, Korean, Serbian and French readers. In 2020, Ret Samadhi was translated into French by Annie Montaut as Ret Samadhi: Au-delà De La Frontière. The English translation by US-based artist-translator Daisy Rockwell came out first in 2021, from Titled Axis Press in the UK. Shree’s first book published there, it qualified for the International Booker nomination. While Tomb of Sand had already begun making waves after the announcement of the International Booker Prize’s longlist last month, last week it became the first Hindi novel to make it to the Prize’s shortlist, which features five other books—Korean, Norwegian, Japanese, Spanish and Polish—in translation.

Soon after the shortlist announcement, Shree spoke to Lounge about her relationship with the process of translation, how she views her bilingualism, and how Tomb Of Sand’s original narrative style came to be. Edited excerpts from an email interview:

To many readers, publishers and fellow writers, you are already a well-regarded author. The shortlist means greater awareness of your work with a certain English-centric section of readers and publishers. In view of this, and in continuation of something you said in an earlier interview—that layers are gained in translation but your own “sounds and smells and tweaks and twirls” are lost—how do you see this wider recognition of you and your work?

I do not mean that sounds, smells, tweaks are lost, but that they are not necessarily the ones with my dhwani in them.

For me, translation is dialogue and communication which establishes a new friendship between the two texts—the original and the translated. As in communication there is something live and electric in what one says and in what the other receives, so it is here. It is not a dead object changing hands but a live and mercurial entity going from one place to another. A rich text becomes differently richer. It finds a new belonging in a new cultural milieu. And it also gives to the new homeland, if you will, cultural inputs from where it has originally come. It really is about a dialogue between cultures which brings to both new ways of seeing, being, expressing.

How active was your involvement with the French translation of ‘Ret Samadhi’? How was each different?

Yes, Ret Samadhi has been translated into French and English (in that order). Given my respect for the autonomy of translation and translators, I cannot be hands-on. It is after a degree of mutual trust, respect and understanding has developed between me and the translator that translation in a different language is begun. Once it has begun, it’s for the translator to decide whether and when she (both the translators of Ret Samadhi are women) needs to get in touch with me for possible clarifications and explanations. That interaction during the making of the translation often turns out to be surprisingly rewarding. Several of the translator’s queries and comments offer clues to meanings and implications of which I had not been aware during the act of writing. This non-interference has been best for everyone.

A lot of Indians grow up at least bilingual, if not trilingual. Sometimes, a lot of this knowledge—of reading, writing, and at least being slightly fluent in our idioms and sayings—is neglected owing to the pressure of jobs, life, and the “convenience” of English. Language is, of course, a practice that needs daily nurturing. Can you talk a little about this?

For Indians, fortunately, it is natural to be multilingual. Our tragedy is that instead of nurturing that, we have let English hierarchise languages in our heads and hearts. English has become the language of success and getting about in the world. Which is fine, but that does not require letting go of other languages available to us. Possessing more than one language has never harmed anyone. It is, rather, a source of great enrichment, given the wealth contained within each, going back centuries. We should celebrate multilingualism, multiculturalism in the world and in our country rather than go astray towards a mono-culturalism, with its totalitarian impulse.

English was the medium of instruction in your education. Did you ever have to “consciously” choose to write in Hindi over English? Or did it come naturally?

Like so many other Indians in north India, I have grown up with Hindi and English. Most of us know English through formal education and Hindi through its informal proliferation in our lives. I think, on balance, the latter turned out better for me because I had picked up Hindi in many registers—the language of conversation within the family, of narrations of our bedtime tales, and the colloquial and lively street language, the exposure to serious, literary, classical Hindi and Urdu via mushairas and kavi sammelans, which were still widespread in my growing-up years in the small and big towns of Uttar Pradesh, and of course the reading that we did where there were still many Hindi children’s magazines available for us.

So, while I did go through some period of wondering and wandering between the two languages for my expression, it more or less quite naturally and intuitively became Hindi for me. This I say without rancour against English—we all write in the language we are most comfortable in.

‘Tomb Of Sand’ flows in poetic, meandering, third-person stream-of-consciousness. It’s almost sand-like—if you are trying to hold on to it and gain immediate meaning or direction, it slips from you. If you stay with it with stillness, the narrative, and the plot, seem to come to you themselves. I am assuming this is true of the original too. Can you talk about this treatment?

You have said it beautifully. That is the fun of (feedback from) readers, because they give the writer wonderful interpretations. What you say makes wonderful sense to me. I have achieved that intuitively, not by following a deliberate formula. The writing process has its own magic. You start off as if you are the controller but the work comes alive only when it acquires its own breath and soul. Once that happens, it takes over, in a manner of speaking, and you flow along with it. You are in a new partnership and sometimes you lead the way, sometimes the work leads, (sometimes) its characters do.

So whatever happened was in the dynamic of the narrative; and it kept happening (as if) that is how (it was meant to) happen.

This interview was first punished in Mint Lounge 15 April 2022